Diary of a Shopkeeper, 17th August

My plans for this week’s column were immediately dropped on Wednesday when I heard of the death of Sonallah Ibrahim. Book-loving friends know how much I admire the work of this veteran Egyptian novelist. Shop customers too, may have heard me mention Ibrahim, because of a tenuous Orkney connection. He’s one of the greatest writers of our time but remains almost unknown in this country. As proof of that, not a single obituary has so far appeared in a UK newspaper or news-site. Let The Orcadian lead the way.*

Sonallah Ibrahim was born in Cairo in 1937, and spent all his life there. Apart from brief stays in East Berlin in the late ‘60s, when he worked as a journalist, and in Moscow in the early ‘70s, when he was enrolled on a film-making course, he rarely left Egypt. This wasn’t because his country treated him particularly well.

As a idealistic, left-leaning youth, he took part in protests against the growing authoritarianism of Egypt’s charismatic leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser. He was arrested on 1st January 1959 and thrown in jail, where he remained for five and a half years. During his time in jail, he suffered brutal treatment and even torture, and saw friends led off to their death at the hands of the authorities.

In 1964, Nasser released Ibrahim and other Communist-sympathising prisoners, in an attempt to ingratiate himself with the Soviet Union. The experience of imprisonment left its mark, not surprisingly, and Ibrahim would return repeatedly in his books to the individual’s struggle for dignity – and life itself – in the face of oppressive political regimes. Prison life convinced Ibrahim that his ideals could better be served by his being a writer rather than a political activist, and the first fruits of this decision was a short novel, That Smell, based on notes taken in prison, and immediately after his release.

The smell of the title was the stench of corruption – moral and political – that assaulted the narrator on his return to society. It shocked contemporary readers, and its writing style was shocking too. He favoured a flat, affectless prose style, written in formal Arabic, but with the bluntness and straight-talking of urban speech.

Ibrahim avoids the classic dramatic structures of traditional fiction. Rather, the drama in his stories comes from the slow accumulation of small, telling details. The repetition at first seems tedious, but eventually becomes terrifying. His approach has something in common with writers like Scotland’s James Kelman, or the Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgård, of whose books the critic James Woods said, ‘Even when I was bored I was interested.’

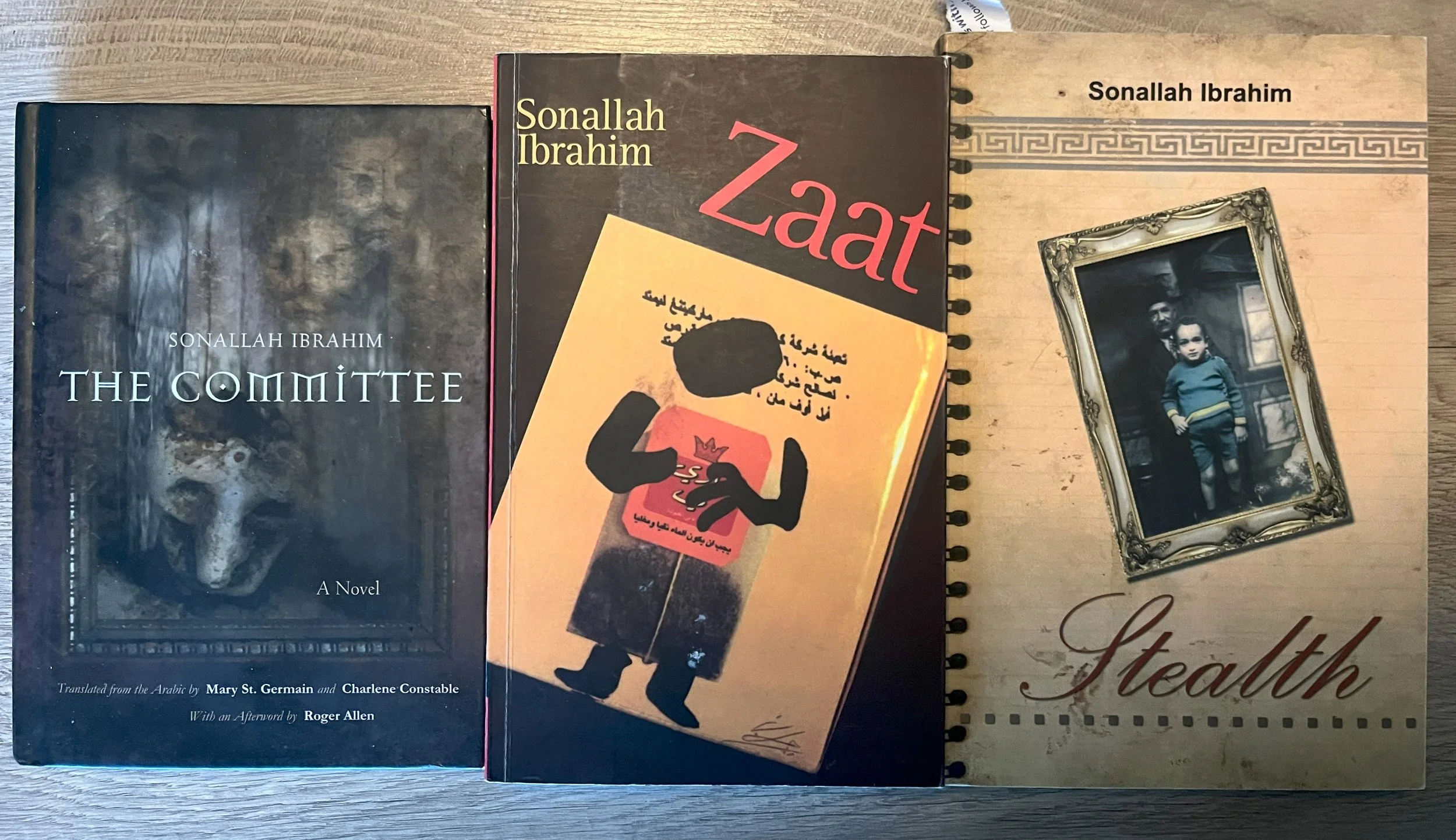

Many of Ibrahim’s books deal with the politics and culture of the Egypt he lived in, especially the repressive nature of successive governments, and the baleful effects of US influence in the Middle East. The Committee is a funny, paranoid fable about a writer arrested for a crime that goes unspecified, but which he must defend himself against anyway. Zaat follows the life of an ordinary Cairo women through a maze of injustice and bureaucracy. Beirut, Beirut follows a writer as he tries to find a publisher for his latest book in the liberal enclave of that city. War and destruction is always in the recent past, or expected to return in the immediate future.

Often Ibrahim quotes headlines and even whole paragraphs from magazines and newspapers from the time he’s writing about. Films and TV programmes are similarly adduced. Everything he writes is fiction, but it’s fiction composed of large chunks of reality, brought together to startling effect. Nowhere is this approach more powerful than in his greatest novel, Warda – which is also where the tenuous Orkney connection comes in.

Warda – meaning ‘rose’ in Arabic – is the code name of a young female fighter taking part in the revolution in Oman in the late 1960s. The sultan of Oman, Said bin Taimur, was a ruler of medieval instincts, dedicated to personal wealth accumulation, and opposing any moves to modernity. Among the 20th century evils he protected Omanis from were sunglasses, radios, medicine and education. The story of the revolution, and Warda’s part in it, is told in two interweaving narratives. The first is the account by an Egyptian writer called Shukri, who travels to Oman many years after Warda’s disappearance (and the failure of the revolution) to try and track down any trace of her.

The other is Warda’s own diaries from the 1960s and ‘70s, preserved by a supporter and passed on to Shukri under a cloak of secrecy. The current Sultan, Qaboos, son of Said bin Taimur, was no more likely to brook rebellion than his father. It’s here, surprisingly, that the Orkney connection comes in. Malcolm Dennison of South Ronaldsay, after a distinguished career with the RAF, became an intelligence officer in Oman, working first for Said bin Taimur and then with Qaboos. A large part of his career involved suppressing rebellions such as the one Warda worked to foment. He never appears in the novel but the works of the sultans’ intelligence operatives are everywhere: a faint Orcadian echo in a far off land.

Sonallah Ibrahim died of pneumonia, aged 88. He was predeceased by his wife, and is survived by one step-daughter.. Nine of his novels are available in English, with another, Star of August, due out next year.

*The New York Times published an obituary later the same day. As far as I can tell, at the time of writing no other English language journal has covered Ibrahim’s death, though it has been widely marked in Arabic news and cultural websites.

The revolution in Oman, as featured in Warda, has been analysed by many memoirists but not many historians. The most thorough and thoughtful account can be found in Abdel Razzaq Takriti’s Monsoon Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2013.) This includes a couple of mentions of Malcolm Dennison’s important but hard to decipher role as a very senior intelligence officer. in Oman. Ron Ferguson’s obituary for Denison in The Herald (5.9.96.) sums up as follows: ‘Malcolm Dennison's precise role in these historic events is difficult to establish; he could only rarely be persuaded to talk of them, and his natural reticence made things even more opaque.’

This diary appeared in The Orcadian on 21st August 2025. A new diary appears weekly. I post them in this blog a few days after each newspaper appearance, with added illustrations, and occasional small corrections or additions.